By Davy Crockett and Phil Lowry

© 2018 Utah Ultras LLC – sharing OK

Introduction: Three soldiers on the Trail

Sergeant Ken Kruzel looked at Specialist Greg Belgarde. Belgarde, an Alaskan Native American, resolutely stared back, but at that moment his face was gushing blood from a spontaneous and prolific nosebleed. Nearly fifty miles into the no-mans-land of the 100-mile distance, Kruzel, Belgarde, and Sergeant Dave Lenau were conserving the precious water in their plastic Army-issue quart canteens. The soldiers, all from Fort Riley, Kansas, were sucking on stones and thinking of being anywhere but this long, dusty Sierra Nevada trail. They saw defeat dripping onto the ground with every crimson drop.

“Hold back your head!” barked Kruzel, willing the blood to stop. Belgarde did his best to stanch the flow. Blood dripped onto his green fatigues and black leather boots.

“Just give me a bit,” protested Belgarde. “I need to sit and get this under control.”

Kruzel pondered. They still had more than 50 miles to go. Time was not a luxury they had, not if they were going to do what no one had ever done before: cover the entire course of the Western States 100-Mile Trail Ride (the equestrian Tevis Cup) from Squaw Valley to Auburn, California – on foot – in less than 48 hours. Even though this was twice the time it took a horse, they could not afford wasted minutes.

Kruzel knew not to leave a buddy behind; everyone in the Army knew that. But the instructions from Major General Edward Flanagan, their Fort Riley commander, had been clear: walking as a group was desired, but the unit’s pride depended on each of them making an individual effort. That was why they were here, after all—to show that the American soldier could cover 100 miles of difficult terrain in less than 48 hours. He weighed his options. Belgarde eyed Kruzel intensely.

“OK, Lenau and I will push on. Do what you can.” Kruzel sighed. His instinct was to stay together. But he also knew that more than half of the original 20 soldiers had either quit or were on the verge of doing so. He also knew that Belgarde was determined.

“Roger that. I can fix it,” responded Belgarde.

A few miles later, as darkness set in, Kruzel and Lenau saw a light approaching from the rear.

“Who is that?” murmured Lenau, wondering if his eyes were playing tricks on him. Kruzel squinted, holding up his angle-head flashlight. A figure approached, the chest of his green fatigues covered in blood, his white teeth flashing a grin. It was Belgarde.

“That,” quipped a smiling Kruzel, “is one tough critter.”

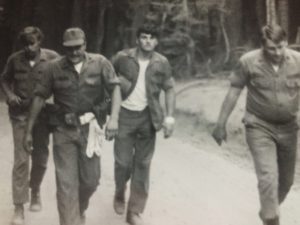

Now reunited, the three moved through the night. They pressed forward, continuing through the next day, and then—another night. They would change their white military socks, which they carried in their pockets or hung from their pistol belts. They developed few blisters. They wore olive drab green military fatigues and wore military issue leather boots. They did not wear packs to carry any extra supplies, and they carried no food. They used the Western States Trail Ride checkpoints to refill their water and wolf down food.

Finally, on July 30, 1972, six soldiers crossed the Western States 100-Mile Trail Ride finish line in 44 hours and 54 minutes. Two hours later, a sympathetic horseman guided another limping but resolute straggler across the line to make it seven finishers.

The soldiers accomplished what no one had done before—they covered the entire Western States course on foot. In doing so, they shattered a paradigm of human performance. Major General Flanagan likely had no idea that the spark of his idea would ignite a prairie fire. He had a vision of what the American soldier could do. The men who carried that vision into action inspired others to continue pushing the borders of possibility. Eventually others followed, creating a new 100-mile trail sport in the process. But these Fort Riley soldiers were the first to cover the Western States 100 course on foot.

This is their story.

Western States Beginnings

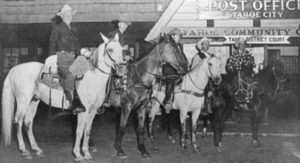

The Western States 100-Mile Trail Ride was founded in 1955 by a group of three riding organizations with Wendell Robie, of Auburn, California the main participant. A charismatic man, he wanted to participate in an endurance contest to ride from Lake Tahoe to Auburn, California, on a historic trail used by gold miners during the 1800s. He knew that this trail rediscovered in the early 1930s would be a significant endurance test for both rider and horse. Robie and four others left Tahoe City early on August 7, 1955, carrying a symbolic mail sack to be delivered to Auburn. The horses moved at a trot over the rugged terrain, averaging 7-12 miles per hour. Along the way, the horses were checked by veterinarians at specified points. One horse (and rider) was withdrawn. The four other riders continued and successfully reached Auburn, about 100 miles away, in 19 hours riding time.

Inspired by this feat, the annual Western States 100-Mile Trail Ride was soon established, which also became known as The Tevis Cup. A perpetual trophy was awarded to the rider who finished first with their horse. But the horse had to be ruled fit at the finish. A sterling silver belt buckle was awarded to those riders who reached the finish at the Auburn Fairgrounds within 24 hours.

By the 1970s, the Western States Trail Ride was known as the premier annual riding event in the country, the toughest in the world. It became widely known, even by some in the military. It became so popular that entries were capped at 250 riders.

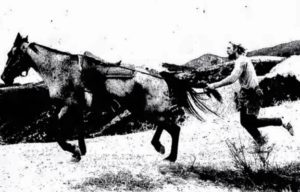

In 1971, Gordy Ainsleigh, an important figure in Western States history, was a large muscular rider. He entered the Ride that year with his horse Rebel. Ainsleigh, weighing nearly 200 pounds, was disadvantaged by his weight. To help his horse maintain speed, Ainsleigh would use a common practice to either run ahead of his horse or behind it, holding its tail. He would do this for many miles. In the 1971 Ride, Ainsleigh finished mid-pack, 48th out of 74 finishers, with a riding time of 19:37, about five hours after the winner.

No one had ever attempted to cover this famous Ride’s course on foot in one go. Who would be the first?

The Infantry Endurance Challenge

The First Infantry Division had learned a lot in WWII, but in 1946, the Army promptly dumped all of its lessons and let the infantry stagnate, excited by other shiny things like nuclear bombs. Then the infantry got whacked on the head in North Korea in 1950. The old lessons needed to come back.

New infantry doctrine after Korea focused on individuals, acting together, as resolute, resilient and resourceful fighting machines. It was no wonder, then, that a guy like Major General Edward M. Flanagan, Jr. would hatch an idea to turn 20 ordinary infantry grunts into an “adventure team” to attempt something that no one thought humanly possible. An adventure team, climbing over the Sierra for 100 miles in military-issue leather boots and fatigues could be viewed as “fun” for recruiting purposes.

Surprisingly, Flanagan’s scheme came together, a classic effective use of the military’s “see the world” bait and switch. Word went out around Fort Riley that there would be tryouts for a new adventure team. Physical fitness was the main selection criterion. Rank was no discriminator. Fifty men volunteered and eventually 20 men were selected to train together as a group. They were assigned to the Sixth Battalion of the 67th Air Defense Artillery Regiment,1ID.

One would think that preparing to march the rugged Western States Ride course would inspire a rigorous training regimen. Not so. There was some group physical training that included 5-mile runs up and down the Kansas “hills” and a few longer hikes. But for the most part each volunteer prepared himself as best he could. In 1972 there was nothing in any handbook regarding how to tackle marching 100 miles. What they were going to do had never been done before. These soldiers were going to prove that a human could cover 100 mountain miles in one go, simply by doing it.

Flanagan believed he could use the Western States 100-Mile Trail Ride to set a standard for the elite infantryman. Captain Joseph McCarthy was one of the leaders on the adventure team. His wife, Mary, had finished the Western States Trail Ride in 1967. McCarthy shared with Flanagan the idea of marching the famed course. Flanagan learned about the fame of the Western States Ride and wanted to co-locate his “adventure team” event with the Ride to test his theory of what infantry could do.

Early in 1972, Flanagan contacted Western States Ride Director, Wendell Robie, about the idea of having his team of soldiers march the entire 100 miles of the famous course. Robie and the rest of his Ride staff were enthusiastic about idea. Robie said he would make a trophy for the first finisher of Western States 100 on foot. In February, news went out about the attempt in the Auburn Journal which stated, “we’re sure the troopers will make it to the finish line, or at least to Michigan Bluff.”

Now, these soldiers were stationed in Kansas. Those familiar with the Western States course can tell you it is not anything like Kansas. Most of the soldiers had never even seen Western mountains, much less been acclimatized to altitude. They had never trained to hike downhill for thousands of feet, an experience one soldier after the fact characterized, correctly, as far harder than climbing, destroying his quads and shin muscles.

A couple of weeks prior to the the event Capt. McCarthy and Lt. Larry Hall went out to meet with Robie to plan the march. McCarthy would be the office in charge and would act as the crew chief. Hall would lead the soldiers on the trail. Thirty soldiers would be involved, 20 to march and 10 to support them.

Trained or not, the soldiers boarded their bus to California in late July, blowing a fair amount of coin and drinking hard on their last stop in Reno, Nevada, before arriving at Squaw Valley. When the 30 men dismounted their bus and gazed on the peaks of the Sierra, they knew they were “not in Kansas anymore.” “We did not expect the terrain to be so difficult,” remembers Kruzel.

The 1972 Western States 100-Mile March

The soldiers arrived a few days before the event, scheduled for Saturday, July 29, 1972. Robie had previously advised the soldiers to start on Friday, to get a one-day head start on the riders, so they could finish with the riders and horses on Sunday. He was concerned that none of the soldiers had experience on the trail and would likely get lost. Jim Larimer, a very fit long-distance runner and rider, was asked to guide the soldiers with his horse the entire way. Larimer quickly accepted the assignment. He met with the soldiers and helped them plan and prepare. Various newspapers got wind of the event and ran an article announcing the surprising attempt to cover the Western States 100-Mile Trail Ride course on foot.

Specialist Joe Hindley, a talented photographer and artist was also stationed at Fort Riley, where he had been painting murals for General Flanagan. He was assigned to travel with the company to photograph the historic event. Robie provided a vehicle and driver that would take him to each checkpoint to take pictures of the men as they came through. Servicemen from a local Army post also came to the event to serve as the groups’ “crew.” At each check point, they would provide food for the soldiers that consisted mostly of freeze-dried Long Range Patrol Rations (LRP), the predecessor for Meals Ready to Eat (MREs).

On Friday morning, the soldiers were ready to leave Squaw Valley. Like any group of soldiers anywhere, the group took on a “Let’s kick this thing’s ass” attitude. Kruzel, however, looked at the peaks with silent foreboding. “This is gonna hurt,” he thought to himself. He caught the glances of Lenau and Belgarde. Their eyes told the same story. “Good,” he thought, “At least someone here has a lick of sense.”

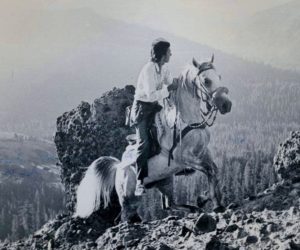

Many of the riders had already arrived and were preparing their horses for inspection. Curious, a number of them watched the soldiers start. The soldiers, guided by Larimer and his horse, set off to a round of big cheers. Immediately they faced a 2,500-foot climb to 8,750-foot Emigrant Pass. Enthusiastic chatter was quickly replaced by labored breathing as they strained to climb in the thin air. Soon the team strung out into different groups, including the trio of Kruzel, Lenau and Belgarde.

Emigrant Pass extinguished any remaining cockiness among them. Doubts arose as they tried to catch their breath in the dry, thin air. Their one-quart canteens were already getting low, even though they were supposed to sustain the men until the first checkpoint, 20 miles forward. Stragglers began to hold up the team. Sergeant Alan Pinciaro, who had just returned from Vietnam, teamed up with two “West Pointers.” This threesome would march together all day and into the night. One of Pinciaro’s companions complained early and wanted to quit after just one mile.

1st Lt. Larry Hall knew that General Flanagan had hoped that the team would stay intact as much as practicable, but that individual effort was to be encouraged and recognized. In the plan drawn up earlier at Fort Riley, Flanagan had decided to compromise, keeping the whole group together for the first 50 miles and then releasing them all to their individual pace. But now, after that grueling initial climb, Hall consulted with their guide Larimer, and it was decided to split up into various three-man units. The leading groups would include those who were the “hardiest,” who could make better time. Kruzel’s trio as likely in close to the front. They continued on as the heat starting to become stifling.

The soldiers continued on through the day upon the high ridges and down into the hot valleys. During the afternoon as Pinciaro and the West Pointers looked down into a beautiful valley, they were astonished to see a bear down below hunting around looking for food. That made them realize that great caution would be needed because “unfriendlies” could be encountered along the way. Pinciaro carried three canteens of water with him, but the West Pointers only carried one each. Both soon became empty. Pinciaro bailed them out by sharing, but before they arrived at the next checkpoint all their canteens were dry as a bone. The West Pointers continued to complain and talked constantly about quitting. Pinciaro became concerned about the very white lips on one of his companions, covered with salt.

Water was a serious issue. Western States Ride veterans had told the soldiers that water would be abundant along the trail, but the summer had been unusually dry. Most of the streambeds were empty. The soldiers’ first instinct was to conserve and not drink to thirst. Sucking on pebbles was popular. Combined with logistical difficulties of getting water and food to the checkpoints, the 20+ mile stretches between aid stations made the situation desperate. One soldier’s account related that 1st Lt. Hall diverted to a stream with several soldiers to get water, then cut back to the main trail. Hall and two others flagged down a logging truck with a handful of canteens to get them to a water source. By all accounts, the water situation was a constant struggle until evening, when the heat abated and the supply problem was solved.

Back at Squaw Valley, the riders spent the day preparing for the Ride and getting their horses inspected. Of the 250 horses present, 169 horses passed inspection. Gordy Ainsleigh was back again this year with his horse Rebel. Also competing was a 17-year-old Hal Hall, seeking his first Western States Ride finish. That evening, at the riders’ meeting, Ride officials announced that the soldiers were on their way to Auburn with a day’s head start. The rest of the evening was spent socializing, dancing, drinking, comparing notes, and speculating if any of the soldiers would really make it 100 miles to the finish in Auburn—a feat all knew no one had attempted before.

While the riders enjoyed a night of revelry, the first of the soldiers arrived at the Robinson Flat inspection station (mile 34) before dusk.

During the evening as Pinciaro and the two West Pointers neared Robinson Flat, they stopped to lay down in a stream to cool themselves off. It was a wonderful cool rest. As they enjoyed the break from the labored march, they heard an alarming loud noise up the stream. With memories of the bear they had seen earlier in the day, all three sprang up with amazing quickness. Pinciaro recalled that he “had never seen men run so fast.” They ran several hundred yards to get away from there fast, becoming runners – not just marchers. Once they reached Robinson Flat, the West Pointers called it quits, but Pinciaro was still in the game.

A total of nine dropped out there, “some suffering severe altitude fatigue sickness, some too dehydrated to go on.” Many had run out of water. At least a couple men had to be taken to the hospital. Larimer used his horse to take one dropping soldier the rest of the way to the checkpoint. Eleven, plus Larimer continued into the evening.

It was soon after this point that Belgarde had his epic nosebleed, and by this time the Kruzel trio had separated from the main group. It is also here that, true to many ultramarathons today, drama entered.

Kruzel (recalling 45 years later) was adamant that his group never stopped to sleep, and that Belgarde caught back up to them before the halfway point. He also claimed that from this point his trio was separate from the main body of remaining soldiers for a time, probably from before Last Chance to Michigan Bluff. (There actually wasn’t a main group at this point as Kruzel had assumed.) Other accounts claim that all the remaining soldiers made it to Last Chance at about mile 40. A number of the soldiers rested there, ate, slept, and then continue on after two hours. One observer stated, “Half the battle was mental attitude. They hypnotized themselves and kept going.”

Various groups of soldiers were still apart from each other between Last Chance (mile 40) and Michigan Bluff (mile 60). The photographer Hindley recalled that it was very stressful on the support crew trying to figure out where all the scattered solders were. Pinciaro, pushing on in the night was frequently separated from all other soldiers now that the West Pointers had given up. At times he would catch up with another soldier, but he continued at his own pace. For him, the trail was very easy to follow and he never got lost. He never was in the group with Larimer and his horse and didn’t even know they had a guide with a horse.

At Last Chance Lieutenant John Mansfield dropped out and about ten miles later Private Theodore Tobey also couldn’t go on.

The Riders Catch Up

Back in Squaw Valley, early Saturday morning the riders drew numbers to determine their starting groups. Young Hal Hall drew group six. At 5 a.m. they were away, staggered by two-minute starts. Hall started out riding fast on his Arabian horse named El Karbaj. He arrived at Robinson Flat (mile 34) in four hours, 25 minutes, in second place, with a group of seven riders. Ainsleigh, with 200 more pounds (horse, rider, saddle, and tack) was going much slower, two hours behind.

The afternoon became very hot, reaching nearly 100 degrees. Hall, eventually in the lead, made the difficult steep climb from El Dorado Creek to the inspection station at Michigan Bluff (about mile 60) during the hottest portion of the day. He was the first of many riders to greet the soldiers on the trail.

A group of worn-out soldiers had arrived at Michigan Bluff right before him around 2:40 p.m. Rider Hall recalled, “They looked a bit whipped. Their faces were blush-red, they were sweaty, and generally looked tired. They were under a shady tree, most of them seated, and some laying on the ground. Some were shirtless as they filled canteens, and wetted bandanas for their heads.” Hal Hall’s good friend and the soldier’s guide, Jim Larimer, was there and looked like the “best of the bunch.” At this point Larimer left his horse Smoke behind and continued without his horse for the rest of the way. After Hall had his horse checked out, and waiting the mandatory hour, Hall continued on and finished the 100-mile ride later that evening, at 9:31 p.m., in 2nd place, with a ride time of 12:51.

The soldiers continued down the trail, and in the late Saturday afternoon, at about mile 70, were greeted by Rho Bailey on her Arabian horse. Bailey recalled, “They were nice, but at that point didn’t look very much like Military men.” Yes, at this point these soldiers didn’t look like Hollywood’s version of soldiers, but all were still very much in the fight, vowing to see it through.

The remaining riders and the company of soldiers continued through the night. The soldiers used flashlights, but the riders usually did not, trusting the eyesight of their horses.

At about mile 79, Pinciaro marched alone through his second night and was the lone soldier at Echo Hills, the 85-mile checkpoint. The local servicemen heated up a pot of water for him and he dumped a dehydrated LRP Ration in the pot. But as he began to eat, his sunburn worn-out lips were burned badly by the hot and salty meal. Quickly after that, he fell into a deep sleep.

By mile 85, there were seven remaining soldiers continuing. One of them, PFC Mike Savage, lagged a few miles behind. Riders, including Gordy Ainsleigh, passed by them all night.

Soon, the soldiers were eager to see their third dawn, a ritual all too common among modern ultrarunners, but an extraordinary first for these men. The dusty chaparral soon yielded to cultivated fields and the lights of homes. The smell of the barn became overwhelming. “Just make it stop,” the mantra of every ultrarunner in the last ten miles of a 100, rang in the head of every man. The road home was not through Berlin; it was through Auburn, California.

The Finish

The rhythmic plod, plod, plod of leather boots dominated the sound of that very early Sunday morning, occasionally broken by a barking dog or occasional clip-clopping of a rider passing by with a “Keep it up!” or “Looking good!” The riders must have shaken their heads–in disbelief, sympathy, or amazement. After perhaps the longest night of their lives, the soldiers saw lights ahead, the unmistakable finish. The lead six soldiers and Larimer entered McCann Stadium at the Gold Country Fairgrounds. Earlier that night, rider Hal Hall had napped after his finish, getting up occasionally to walk his horse so it would not stiffen up. He hoped to see the soldiers’ arrival and was awake when they came into the lighted stadium. Cheers went up with congratulations all around. Their finish time was 44:54.

Still out on the trail, PFC Savage made painfully slow progress. All of the horses had passed him, and he was greeted from behind by a rider making sure everyone made it off the course safely. This “sweeper” greeted him from behind, got off his horse, and walked with the limping Savage to the finish. A “trail angel” if there ever was one. Savage finished in 46:49.

Back at the Echo Hills check-point, a serviceman finally woke Pinciaro up. The sleepy, exhausted soldier was told it was all over and that he had reached 85 miles. Pinciaro was very disappointed that he came so close but did not finish. But he was relieved that his “march of torture” was over and was taken to the local Army post to clean up and rest.

With this, The Big Red One soldiers became the very first persons to cover the Western States 100-Mile Trail Ride course on foot. They were 1st Lt. Larry M. Hall, SP4 Gregory Belgarde, SGT Michael Paduano, SPC Jon Johanson, SGT David E. Lenau, SGT Kenneth Kruzel, and PFC Michael Savage. Their guide, Jim Larimer made it possible. Although he rode a portion of the way, he received a special gold star for being their faithful guide.

The soldiers’ feat invoked surprise at the finish. “All were tired and footsore, but otherwise in good shape.” One soldier said, “It’s a once in a lifetime thing! I’d never do it again unless I had to, but what a great sense of satisfaction to have finished.” To a man, none ever did anything like it again. They reveled in their accomplishment but much later looked back on it with a shudder, like many soldiers do when surveying their careers and combat deployments. “I have no regrets that I did it, but I will be damned if I ever do it again.”

After their finish, some napped, but not all. Lenau was so energized that he could not sleep. He was confused that his exhaustion would not yield to sleep. It took 45 years for him to understand, when interviewed for this article, that these feelings were totally normal for a 100-mile ultramarathon finisher.

Later that night, a banquet was held at the Home Economics Building on the Auburn Fairgrounds. The 93 rider finishers received their belt buckles and the soldiers received a special plaque, recognizing the “First Auburn Endurance March.” The plaque was presented to 1st Lt. Hall by William Penn Mott, the State Director of Parks and Recreation. The Army awarded additional commendations and medals. The soldiers also received replicas of medals awarded at the Squaw Valley Olympic Games. Wendell Robie, the founder and president of the Ride presented the first six tied finishers with the first-finisher trophy and stated that he hoped another group of soldiers would return the next year. The Fort Riley Post stated, “This was the first time the trail had been competitively traveled on foot with a time factor involved.”

The soldiers were granted a one-week pass–perhaps their sweetest reward. Lenau visited family in Missouri. Kruzel, sore from the march, had intended to go fishing in Oregon, but ended up recuperating for most of his leave. Best laid plans of mice and men . . . and ultramarathoners.

Why has this story never been told?

Telling the soldiers’ account is a rescue mission-–to recover a truly extraordinary feat from the dustbin of history. The soldiers’ exploits did not immediately spark the new sport of 100-mile trail ultramarathons. The memory of their accomplishment quickly began to fade away. But why?

So, why didn’t other runners take notice? Here are a few reasons. Their guide, Larimer, while both a runner and horseman, was modest and not given to self-promotion. He remained largely silent about the historic event and it is unclear if he also covered the entire course on foot that year. Later in life his passion was to develop trails in the wilderness that could be enjoyed by all. He passed away in 2013. Guiding “The March” was an asterisk on his riding and running resume, not a featured exploit.

Where were the other ultrarunners at that time? They were mostly running on roads and tracks far away in the Eastern United States, not seeking out the challenge of trails or mountains. They never heard a whisper about this accomplishment.

As for the soldiers, they generally are the worst self-promoters. Part of this stems from a unit, not individual, mentality that is ingrained into the American soldier. Ask any combat veteran recognized for doing something heroic and he or she will say “Anyone else would have done it.” To boot, soldiers see their lives as transitory. A squad bonded together today by common achievement will tomorrow be disbanded for new individual assignments. Members often don’t even stay in touch. To do so invites frustration, or even sorrow. Until today no one had seen the need to tell the story.

Finally, the soldiers, like Larimer, were not vested in what their accomplishment meant. There was no realization that from the March a new sport might be born, no more than Stonewall Jackson’s foot cavalry realized they were setting a new standard for infantry.

Gordy Ainsleigh runs Western States

After the 1972 March, it took two years for someone to follow in the soldiers’ pioneering footsteps. In 1973, Ainsleigh participated in the Ride again, but his horse became lame and he didn’t finish. He gave away that horse and didn’t acquire a new horse in time to enter the 1974 event. Remembering what the soldiers accomplished, and knowing Ainsleigh’s running ability, Ride staff encouraged Ainsleigh, their friend and colleague, to just “run it.” He accepted. The added wrinkle, however, was that he wanted to meet the 24-hour Western States Trail Ride cutoff and earn the belt buckle award.

Amazingly, he pulled it off, despite many doubters, finishing in under 24 hours. Rider Hal Hall won the Tevis Cup that year and was again walking his horse in the early morning when Ainsleigh came into the stadium. Just before the finish line Ainsleigh did a somersault in celebration.

Three years later, in 1977, the first Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run was founded by Wendell Robie. Ainsleigh was credited as the first to cover the course on foot. While the establishment of Western States was not the first 100-miler, it captured the imagination of runners all over the country. Other trail 100s would also be quickly established following the lead of Western States. Today more than one hundred 100-milers are competed on trails in the United States each year by thousands of runners. Credit goes to Western States 100 for making this impact on the explosion of 100-mile trail running.

Legacies fade and grow

As the soldiers’ legacy faded, Ainsleigh’s grew. In 1978 the Auburn Journal falsely mentioned that Ainsleigh was “the first man ever to finish the 100-mile course,” and in 1979 hailed him as “the first man to take the course on foot.” Today his famed 1974 run is probably the most legendary story in the ultrarunning sport, and he is credited as being the first, the one who started it all. He doesn’t dispute this, having claimed he invented the sport. Ken “Cowman” Shirk was the next person to complete the course in 1976 in a time of 24:30. Shirk also figures prominently on the Western States Endurance Run (WSER) history website, even though Shirk’s run exceeded 24 hours. In 1978 two runners are listed in the official results who finished in nearly 39 hours. It is curious that the soldiers are not listed as finishers in 1972.

As of 2018, there was no mention of the soldiers in late 1970s accounts, modern anecdotes, or official modern statements from the WSER. No public statement from Ainsleigh has recognized that others covered the course on foot before him. Prior to the release of this article, the WSER website did not mention the March, and credited Ainsleigh and others as the first to cover the course on foot. The 2018 official Western State Endurance Run Program stated falsely that Gordy’s run marked “the first time anyone had successfully completed the route from Squaw Valley to Auburn on foot.” All of the WSER founders had either forgotten, misremembered or discounted the importance of the March that they all had witnessed.

In a 2017 interview for this article, she admitted that the founders “propped up” Ainsleigh as the race’s “icon” and wanted to “make sure his place was cemented in history.” Perhaps making the story of the March public could have challenged Ainsleigh’s legacy, which WSER wanted to protect. When asked why the story of the March had not been told publicly or acknowledged by WSER, she said that the story wasn’t viewed as significant to its history. She did not want it even mentioned with the Run’s history.

Weil’s 2017 account acknowledged that the March occurred but downplayed it. Her recorded remarks in 2014 were openly critical of the soldiers and she poked fun about these decorated war veterans and of their attempt. In that presentation, she repudiated the soldiers’ claims that they actually finished. She said that she had called Jim Larimer a couple years earlier to ask about the March. She claimed that in that call Larimer said that every one of remaining soldiers on the second day rode on his horse at one time or another. That would have been impossible because they were never all with Larimer.

Weil’s narrative describing cheating suffers from several credibility flaws. First, Jim Larimer passed away one year earlier and was no longer available to verify what amounted to hearsay. Second, the soldiers were split up in groups of three before Emigrant Pass. They were never all together with Larimer. Remember also, that the horse was left behind at about mile 60. Third, the soldiers understood the integrity of their mission to cover the entire course on foot. Every one of them could have faced discipline from military authority had they cheated and attempted to cover it up. Fourth, not a single contemporary account reflected any cheating, even from riders who passed the soldiers and would have been eyewitness to cheating. Fifth, every soldier interviewed was credible in his present-day account and had no motive to lie, either then or now. Pinciaro, who reached mile 85 did not even know they had a guide with a horse. No money or fame was at stake, and the consequences of cheating, as mentioned, were much more severe than an embarrassing headline a newspaper. Sixth, Wendell Robie and the Ride officials endorsed the results, along with Larimer who stood next to the finishers at the banquet when they received their finisher awards. These accounts were corroborated by modern-day interviews. None of these individuals, especially Larimer, along with the soldiers, had any motive to cover up any cheating.

Finally, Weil in her passion for WSER history, more than 40 years after the fact, may have wanted to deflect the significance of the March: to cement Ainsleigh’s legacy, as he was instrumental in laying the groundwork for the WSER. The legend of the “first run” added to WSER’s mystique and appeal, and rewarded one of WSER’s tribe. Weil’s claim, standing in stark contrast to every other contemporary and modern account of the March, perhaps explains why history was at best forgotten or at worst, revised: because of that most common of human traits, tribal loyalty. The founders of WSER were all Western States Riders. Ainsleigh was one of their own. He was given credit for being the first, which suited them fine, since he marketed the stuffings out of the emerging Run. But they all knew that Ainsleigh was really the eighth to cover the course on foot. Ainsleigh’s efforts to build and grow the emerging sport of 100-mile trail ultrarunning (which to his credit were laudably significant) eclipsed the original inspiration from the 1972 March. The soldiers were, after all, outsiders who came, finished the course, and then left. There was no good reason to remember them.

After this article was published, Weil argued strongly over social media that the March had no place in Western States Endurance Run history because it happened before 1974. That made no sense because the Run wasn’t founded until 1977. She forcefully proclaimed that Ainsleigh was the “founder of the Run” which is not accurate, Robie was the founder. He authorized WSER to be held starting in 1977, put his resources behind it, and by 1978 organized the first board. Two weeks after this article was published, the WSER.org website’s “How it all Began” page was updated with a short mention of the event, downplaying it because “details of the hike are sketchy at best,” (despite this 7,500-word article and all the 1972 newspaper articles published in the Auburn Journal about the March) and it implied that the soldiers cheated. It is sad that WSER, even today, cannot just embrace this historic event like their founder Robie did.

No matter the motives of WSER officials, then or now, there is no question that the Western States Trail Ride (Tevis Cup) and Wendell Robie were visionary and gracious in accommodating the March. The Ride staff were experienced in putting on 100-mile endurance events and knew better than anyone how to transition to support ultrarunners. Their experience created the cradle into which modern 100-mile trail ultrarunning was born. Putting the March into its proper place in history is not an easy task, or one devoid of passion, but it remains important, just as much as recognizing Robie for his vision of distance performance. (For more details about the history of the Western States Trail Ride and its impact on ultrarunning, see Endurance Riding – Part 2 (1955-1970) and Endurance Riding – Part 3 (1971-1979)

Forgotten no more

As for the soldiers, most of them left the Army within a few years of the March, losing contact with one another. Some have died. Regrettably, the infantry ideals envisioned by Flanagan and demonstrated by the soldiers have been validated by Taliban adversaries in Afghanistan. Endurance on foot is now a modern creed of the infantry soldier. There is no evidence that the evolution of infantry ideals can be traced to the March, but it certainly foretold what the infantry would need to become.

Today, Dave Lenau is close to retirement from his civilian career, and he reflects on his achievement as he takes walks with his disabled son in the Missouri countryside. He doesn’t really appreciate what he and the others did, which explains much. While it meant a lot to him personally, he was content to allow it to be forgotten.

Michael Paduano, one of the finishers, was born in New York. He was a Vietnam veteran. After he left the service, he went into construction and was an avid New York Giants fan. He settled in Virginia and passed away in 2012 at the age of 60. He left behind a wife, two sons and four grandchildren at the time of his death. He had told his son about the march and always said that “it was test of heart, either you wanted it or you didn’t. He also said he just loved the brotherhood of all those who were with him.”

Alan Pinciaro left the service in 1974 and pursued a career in construction as a truck driver and heavy equipment operator. He has Boston roots but now lives in Maine. He and his wife have three beautiful daughters, eight grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren. When told that someone wanted to talk to him about the March, he searched his memory and started to laugh. He had never heard of the Western States Endurance Run, but was thrilled to learn that he was a pioneer of the Run.

Robin A. Sampson made it to about mile 75-85 and then dropped out. He was from Montana and died in 2000 at the age of 52. At the time of his death, he left behind a wife, two sons, three stepchildren and a granddaughter. He never mentioned the March to his sister.

Edward M. Flanagan Jr., the founder of the Fort Riley adventure team, retired from the military in 1978 after 36 years with the rank of Lieutenant General. He went on to author many books and was recognized as the nation’s leading authority on Airborne history. He settled in Beaufort, South Carolina where he died at age of 98 in 2019.

The soldiers of the Big Red One shattered paradigms in multiple worlds, blazing trails as veritable pioneers for a new sport. They were the first finishers of Western States 100. They were the first 100-mile trail ultramarathoners of the modern age. And, now, they are absolutely not forgotten.

About the authors.

David “Davy” Crockett has finished 108 100-mile races. He entered the sport in his mid-40s but still was able to excel and win a few 100-mile races. He is the director of the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame. He is a historian of both American history and of ultrarunning history and has written six books and published articles in many periodicals. During his research of the history of horse endurance riding, he discovered the forgotten first finishers story covered in this article. He has a podcast, Ultrarunning History Podcast at ultrarunninghistory.com

Phillip “Hyperphil” Lowry has finished about 70 100-mile races, including 20 finishes of the Wasatch 100 and 15 finishes of the Bear 100. He has earned sub-24 buckles at Wasatch, the Bear and Black Hills. Most recently he won the Masters title at the Bigfoot 200 Mile Endurance Run. He was deputy general counsel to and a Major in the Utah National Guard, and he deployed with the Special Forces to Operation Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan) in 2012-13. @hyperphil

Sources:

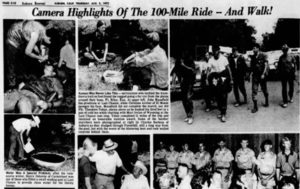

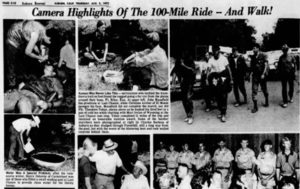

- Auburn Journal, Aug 3, 1972, Section C, “Camera Highlights of the 100-Mile Ride – And Walk!”

- Auburn Journal, Feb 24, 1972, A-10; Jul 13, 1972, A-10; June 19, 1978, A-8; June 23, 1982, C-1.

- Reno Gazette-Journal, Jul 14, 1972, 5; Jul 31, 1972, 15; Aug 3, 1972, 13

- Fort Riley Post, “Seven Air Defenders finish 100-mile hike,” August 11, 1972, 1-2

- 2017 interview with rider, Hal Hall, 30-time finisher and past member of the Western States Trail Foundation.

- 2017 interview with rider, Rho Baily, past member of Board of Governors for the Tevis Cup.

- 2017 interview with Shannon Yewell Weil, co-founder of Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run and Trustee for 30 years.

- 2017 interview with finisher, Ken Kruzel

- 2017 interview with finisher, David Lenau

- 2018 interview with photographer, Joe Hindley

- 2018 interview with soldier Alan Pinciaro

- 2014 Western States history presentation by Shannon Yewell Weil at the 2014 Western States Training Weekend. This Will Never Catch On: The birth of an Icon

- Results and history of the Tevis Cup

- 2012 Gordy Ainsleigh podcast

- Bill G. Wilson, Challenging the Mountains: The Life and Times of Wendell T. Robie

- Western States 100-mile Endurance run website

- Western States Eundurance Run 2018 Program

- Obituaries for Gregory Belgarde, Robin Sampson, and Edward Flanagan