Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 14:42 — 16.4MB)

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music | Android | Pandora | iHeartRadio | JioSaavn | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | RSS | More

By Davy Crockett

![]()

![]()

For the common man, we frequently make history without knowing it at the time. As years pass, one can look back and discover that certain events, which at the time seemed insignificant, actually played an important part in history. Such events weren’t forgotten or pushed aside; their stories just had not been told. Such is the case with “The Last Day Run.”

Ultrarunning existed in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The participants were mostly professionals who performed for spectators. As the Great Depression hit, events for professional ultrarunners dwindled and dried up in America. But rising from the tragedy and ashes of World War II, ultrarunning events slowing appeared again, but this time for amateurs looking to test their endurance. They were first hiking events such as the Padre Island Walkathon (110 miles) of the 1950s in Texas, and the JFK 50 starting in 1963 in Maryland. But soon running events surfaced and the term “ultramarathon” was first used around 1964.

Absent in the pages of very early American ultrarunning history is the story of the “Last Day Run.”

| Please consider becoming a patron of ultrarunning history. Help to preserve this history by signing up to contribute a little each month through Patreon. Visit https://ultrarunninghistory.com/member |

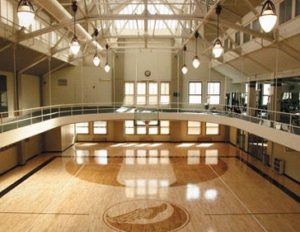

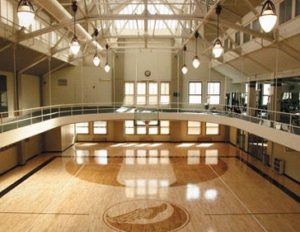

The Los Angeles Athletic Club

The Los Angeles Athletic Club (LAAC) was established in 1880, the first private club in the city. Monthly dues were $1 per month that first year. In 1912 the club’s new home was established downtown in a 12-story building with an indoor swimming pool on its upper floor which caused quite a stir. In the 1950s the downtown club was modernized and by the 1960s an indoor, 165-yard rubber tartan track was built on the 7th floor. The indoor track would be the site of 1960’s ultrarunning history.

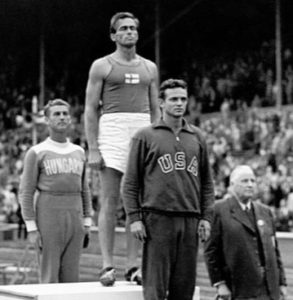

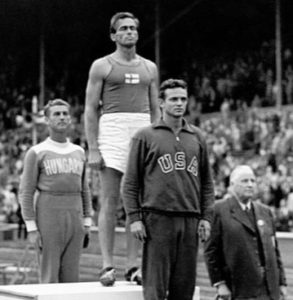

Steve Seymour

Steve Seymour (1920-1973), was an elite javelin thrower. He spent 1946 in Finland training with that nation’s world-class throwers. In 1947, he established an American record of 75.80 meters, within ten feet of the world record, which opened the door for him to compete at the 1948 Olympics where he was awarded the silver medal. In 1950 Steve achieved his third national championship in the event and in 1951 he was the silver medalist in the Pan American Games. Steve became a physician. He practiced as an osteopath and also operated a clinic for alcoholics. In 1965 Dr. Seymour didn’t realize it, but he became an American ultrarunner pioneer as a long-time influential member of the Los Angeles Athletic Club.

The Last Day Run Begins

The year was 1965. Steve Seymour arranged to put on a 24-hour race at the indoor Los Angeles Athletic Club. It was called the “24-hour Last Day Run” and was held on Halloween. This event was very significant to American ultrarunning history for many reasons, the first being that it is believed to be the first modern-day American 24-hour race. Steve started the enthusiasm for this event by participating in it and going the furthest distance. It all started at 12:00 a.m., early on October 31, 1965. Steve ran 50 miles in 17.5 hours.

Why was it held on Halloween, and why was it called “Last Day Run?” The event was called “Last Day” because it was associated with an annual 30-day “jog” competition that originated in California. This event was established in 1964 by the Olympic Club of San Francisco. Runners would run for 30 days in October. The club would award trophies to the running club with the highest total mileage, with the most participants, and with the highest average miles per person. In 1964 the LAAC participants totaled 3,897 miles. Steve Seymour decided to establish the 1965 “Last Day Run” to help the club competitors pile up miles on the last day of October.

Lu Dosti

Luan (Lu) Dosti (1927-1992) was an aerospace engineer and in his youth an Albanian soccer player. In 1968 he was a serious chain-smoker, enjoying a sedentary life as a student, husband, father and businessman. “He’d sit back and chuckle at the joggers on the track at the Los Angeles Athletic Club” where his daughter would swim and his wife worked out. Lu was warned by his doctor to lose weight and stop smoking. He had turned 40 and had not run long distance since his high school days. (“The Loneliness of the Long Distance Jogger” Los Angeles Times West Magazine, Jan 10, 1971).

Lu decided it was time to shape up. First, he tested his endurance by attempting to run a half mile on the 165-yard rubber tartan indoor track at the club. He only made two laps before scrambling back to his chair. But he didn’t give up. Within a month he ran non-stop for a mile and vowed to stop smoking. Three weeks later he ran “pier-to-pier” at Santa Monica Beach. At the end of his run, he smoked his last cigarette. By June 1968 he could run five miles. In October 1968 Lu naively decided to participate in the month-long “jogging event” at the LAAC, which was the defending champion club. Lu hoped to beat the 805 miles run in 1967 by club champion, Bud Murphy. As the month went on, Lu turned to the founder of the “Last Day Run” Steve Seymour for coaching. Steve was surprised with Lu’s current endurance and encouraged him to try for 50-60 miles at “Last Day Run.” Lu hoped he could do that, but primarily had his sights on staying ahead of the previous year’s champion, Bud Murphy, in the overall month competition.

Bud Murphy

Bud Murphy was a 41-year-old advertising executive and long-time amateur athlete. Lu’s wife wrote that Bud “was pretty. A strapping 6-foot plus, strawberry-blond, baby-blue-eyed Peter O’toole.” In contrast she described Lu as “a 5-foot-9-inch thinning-down-all-the-time Omar Sharif.” (“Tortoise and Hare Revisited,” Los Angeles Times, Nov 7, 1968)

Previously, at the 1967 Last Day Run, Bud reached 100 miles in less than 24 hours. His accomplishment was one of the early sub-24-hour 100s, in less than 24-hours, in an organized race, in the modern ultrarunning era. Bud was determined to defend his championship and perhaps run 100 miles faster in 1968.

1968 Last Day Run

The day for the 1968 24-hour Last Day event arrived. It turned out to be a duel between Lu and Bud. Lu was still a rookie on nutrition and ate only one significant meal during the run, ending up losing 20 pounds. He was surprisingly in the lead at 67 miles. More experienced Bud soon took over the lead and was ten miles ahead of Lu when he reached 90 miles. Lu didn’t sleep at all and developed tendonitis in both feet. At one point, Lu said, “I quit.” But his coach and race director, Steve Seymour, pushed him back on the track. At the same time Bud had stomach issues and kept throwing up. He also returned to the track “running like a gazelle.” Steve provided all the runners chicken soup and malted candy, to stock the first American modern-day aid station.

That day, Bud reached 100 miles in 21:36, breaking his 100-mile PR, and then quit. Lu ran 93 miles but achieved his goal as the club’s overall month winner with 792 miles, 57 more miles than Bud. The newspapers reported that Bud set a 100-mile “World Record Jog.” It could have been a world modern indoor best. For outdoors, it was not even close. Earlier in 1968, Dave Box of South Africa set a new 100-mile world best of 12:40:48 on a track. Bud’s performance was likely an American 100-mile best for the modern era.

With each additional year, the focus of the “Last Day Run” evolved into a quest to reach 100 miles. The “Last Day Run” held on this indoor track in downtown Los Angeles had given birth to the modern-day American 100-miler ultramarathon. For the next couple of months, newspapers across the country reported on Bud’s historic 100-mile achievement.

Mihaly Igoli

Mihaly Igoli was a Hungarian distance running coach. He was a notable runner in Hungary and participated in the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin. Over the years his running students would set 49 world records. After the 1956 Olympics in Melbourne he decided not to return to his homeland which had just been crushed by the Soviet Union. He went to the United States and eventually ended up in Southern California where he coached the Los Angeles Track Club. One of his famous students was Jim Beatty who was the first to run a four-minute mile indoors. In 1969 Lu approached Mihaly for coaching help. Mihaly at that time was coaching at Santa Monica City College and he agreed to let Lu join his group. He put Lu on a rigorous interval training program and added swimming to increase Lu’s heart capacity. “Lu learned to push fatigue to its limits by running when the inclination was to stop. He learned that pain was no excuse and the time to bear down was when the pressure was greatest.”

1969 Last Day Run

Lu also ran regularly with Dr. Myron Shapiro, and another new runner, Miki Gorman. For the 1969 “Last Day,” Lu vowed to not waste any time and would forgo long meal breaks and instead stop once per hour for 15-30 seconds to gulp down Gatorade or drink some tea with honey. That year Lu won with 111 miles in 22:35 and lost “only” 15 pounds this time. He recorded 911 miles for the month. Lu thought he had set a world indoor 24-hour mark, but later learned it was held by an Englishman with 120 miles. Lu now set his sights on the 120-mile mark.

1970 Last Day Run

Lu’s training for 1970 was serious. He changed his diet from mostly meat to fish, fowl, and vegetables. There were no more blood-red two-inch steaks. Instead of being pushed by another runner, he forced himself to run the long daily miles during October, alone on the UCLA track. Every morning Dr. Shapiro would give him a wake-up call at 4 a.m. Lu ran about 30-40 miles per day that month. He took the advice of the USC head swim coach, Peter Daland, to rest the next-to-last day. That day he spent long hours sleeping, massaging his legs, and eating homemade chicken soup.

The participation of club members in the 30-day run greatly increased to 600 men and women in 1970, who would record 28,000 miles of running during October that year.

The historic 1970 “Last Day Run” arrived. Lu’s fifteen-year-old daughter and nine-year-old son also entered the event. Lu’s plan was to take 10-15 second breaks every 5-10 miles. He fueled on tea with honey, consommé (soup), water and juices. The only solids he ate was “custard spiked with protein powder.” He also took salt and dextrose tablets every 30 minutes. His wife, Rose, crewed for him, handing him on the run “spill-proof laboratory urine bottles which made drinking on the run easy.” She complained in fun about crewing for him. “Next time he’d better have a paid pit man around. Serving up drinks from urine bottles every 10 to 15 minutes to a runner doing 43-second laps is no joke. It takes that long to pour. Lu took most of his nourishment on the run. It was like handing a surgeon his tools on a roller coaster.”

The race began at midnight as music played over loudspeakers. About a dozen runners took off. At night looking up to the windows the place looked like “a giant lantern with joggers ambling across the moonlit windows like black cats.” Lu led the pack of felines and reached 50 miles in 8:30. Any rest times were cut down to five minutes max. After 12 hours Lu turned into the typical ultrarunning grouch and started demanding “more water, proper drinking cups, apple juice” etc. Apple Juice? They didn’t bring any. Rose quickly went out to buy some. When she asked him if he wanted anything else, His reply was, “Yes, new legs.” His young son ran 200 laps and then fell asleep on his mat. One observer said, “I’ve seen kids sleep with teddy bears, but never with lap counters.” (In those early days, recording laps were casual. Each runner kept track of their own laps with lap counters.)

Lu, at the age of 43, ran 100 miles in an incredible 17:30. He went on and finished with 127.4 miles in 24 hours, which was thought to be a world indoor 24-hour best, and an American 24-hours best on all surfaces. He actually stopped around 22 hours. He later said, “It may not have been the best time of an indoor track, but it’s a hell of a good time for someone enroute to 127 miles.” Lu finished the “30-Day” with 1,040 miles. During his race, Lu consumed 50 bottles of tea, 50 bottles of water, and 25 bottles of juice. He developed only a few toe blisters and lost over seven pounds. But the big casualty was losing seven toenails. (“The Loneliness of the Long Distance Jogger” Los Angeles Times West Magazine, Jan 10, 1971).

But the truly historic event on that track during the 1970 “Last Day Ran” didn’t involve Lu.

Miki Gorman

Miki (Michiko) Suwa (1935-2015) was born in China to Japanese parents. In 1963 she moved to the United States, attended college, married businessman, Michael Gorman, and moved to Los Angeles where she became a secretary for a Japanese trading company. In 1968, she bought a membership in the LAAC where she enrolled in a calisthenics class. She was offered the choice of a stationary bike or jogging to warm up. She chose running, and for the next five years the LAAC track was her running home. She explained, “The club was like home to us, and the other runners were like family.” She developed a great running comrade with Lu Dosti and Myron Shapiro.

Miki trained hard. She said, “I like to do hard things, My mother would deliberately put foods I didn’t like in my lunch bag to teach discipline.” One of Miki’s mentors encouraged her to enter the 1969 “Last Day Run,” which would be her first race at any distance. (Miki Gorman, “As the Miles and the Years Pass By,” The New York Times, Oct 30, 2005.)

During October 1969, the runners would post their laps on the wall of the club each day. Miki explained, “That’s how I started as I am a very competitive person. I was the last person after the first week. Then I got more interested and by the end of the month, I was in second place among the women.” Miki’s plan at 1969 Last Day Run was to run 50 minutes and rest 10 minutes every hour, with a two-hour lunch break at 12 hours. She ended up running fantastically and finished with 86 miles. The next morning, she said, “I feel fine. I’m just a little tired. I’ll nap later.” She explained, “That’s how I started [running races] as I was very, very competitive.” Her 86 miles was believed to be a woman’s world best for 24-hours. She ran 590 miles during that month. (“She Ran 85 Miles As They Ran Around the World in One Month”, Red Bluff Daily News, Jan 8, 1970).

Miki started serious training. She joined Lu in being trained by Mihaly Igloi. “He didn’t let us stop. We were always jogging. We had a hard time understanding each other. He would have us do an easy jog, then shake out strides, then some at eighty percent. Then we would do repeats for two miles, then 150-yard runs, then some jogging that got faster.” Miki became a fixture on the track at the club, running circles for hours. “When I was working people would ask me why I was running, as everyone was very interested as to why a woman would run in 1970.” She worked days and had a hard time sleeping during the night because of swollen feet. (Gary Cohen interview, 2014).

1970 Last Day Run

Miki made ultrarunning history at the 1970 Last Day Run. She covered 100 miles in an astonishing 21:04:04. A minute after Miki finished, after running the 1,075 laps, she collapsed and said, “I don’t think I can run anymore.” (“Runners Claim Records For 100-mile Marathon,” Associated Press, Dec 3, 1970.)

In 1973 Miki would also set the woman’s world’s record in the marathon with 2:46 and a world’s best for the half marathon in 1978 of 1:15. Her personal best in the marathon came in 1976 with 2:39. Unfortunately the women’s marathon was not included in the 1976 Olympic Games when she was at her peak. She was the only woman to win both the Boston and New York City Marathons twice. In 2001 she was elected to the Road Runners Club of America Hall of Fame. For her, it all started at the “Last Day Run.”

Miki Gorman passed away in 2015 at the age of 80.

Lu Dosti passed away in 1992 at the age of 65.

Dr. Steve Seymour passed away in 1973 in Los Angeles at the age of 52.

Mihaly Igloi, who coached both Lu and Miki passed away in 1998 at the age of 89.

The Last Day Run’s Historic Impact

It is unknown how many more years that the “Last Day Run” was held. 1972 was likely the last year with Steve Seymour’s death in 1973. But that event which was competed on the seventh-floor track of the Los Angeles Athletic Club was the site of some of the earliest American ultrarunning records and the first known official modern-day American 24-hour race. Note: Nothing below was of course certified. There was no governing body yet over these events and the runners kept track of their own laps with lap counters that they carried with them.

- First modern-day American 24-hour race – 1965

- World indoor track 24-hour best, American modern-era 24-hours best, 127.4 miles, Lu Dosti – 1970

- World woman’s 100-mile best, 21:04:04 – Miki Gorman – 1970

- American woman’s 24-hour best, 100 miles, Miki Gorman – 1970