It was just announced that Nick Marshall is the 2017 inductee to the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame. He was one of the elite 100-mile runners in the late 1970s and early 80s. Here is a chapter about Nick from my free online book, Swift Endurance Legends. Nick helped me extensively with this book to help preserve the history of 100-mile ultrarunning.

———————————————————————————————————————————————-

Nick Marshall, of Camp Hill, Pennsylvania has finished 100-milers across a span of more than 38 years. In addition to his running achievements, he left a huge mark on early ultrarunning through his efforts as a historian and record keeper.

Nick started running marathons in 1973. He realized that the longer the race, the better he could compete. He said, “I was motivated by a simple curiosity over a basic question: How far can you go?” He set his marathon PR of 2:41:15 in 1975 at the Harrisburg Marathon.

Nick’s introduction to ultras came in 1974, at the C&O Canal 100K on a point-to-point course from Washington D.C. to Harpers Ferry. He averaged 8:12 for the 62.1 miles while finishing in second place to Park Barner. He was then hooked on ultras. In 1976 he broke 6 hours for 50 miles three times, winning the Ft. Meade 50 in 5:54:08 and placing 5th in 5:51:38 in the national championship at the Metropolitan 50.

Starting in 1976, Nick, like most other ultrarunners of his time, made his way to Lake Waramaug in Connecticut to run the 50 and 100k. In 1976 he finished 2nd in the 50 with 5:56:05. In 1977, the race was a showdown between Nick, Park Barner, and Don Choi who were the fastest 100K runners in the country at that time. Don was the early leader but Nick passed him at 35 miles and then pulled away, reaching 50 miles in 5:42:31, and going on to also win the 100K in 7:17:06. Don and Park came in 23 and 27 minutes behind him. At that time, this was the second fastest 100K time ever recorded in the country. He returned to the race in 1978, running 6:17:40 and 7:56:22.

Nick is one of only a handful of men who have broken 6 hours for 50 miles on both the road and track. At Santa Monica, Cal., in 1977, he did his fastest track 50 with a time of 5:43:17 which earned him a bronze medal in that year’s national championship.

Unlike some runners, Nick was never good at recovering quickly from a hard ultra, but in this instance he entered the Lake Tahoe 72-mile which was held just 13 days later. After a rugged start, he rallied to win the event consisting of a single circuit of the big lake. Nick wrote an article for Runner’s World magazine about what was a scenic and memorable experience. It was titled “Super-Lap,” and a reader in Tennessee later said this article was the first he’d ever heard about such a thing as an ultramarathon and it helped inspire Gary Cantrell to become involved in the sport. Cantrell went on to become famous in our world, as a beloved race organizer, superb writer/raconteur/storyteller, and a sage philosopher of endurance and perseverance.

Later, a hip injury sidelined him from ultras for more than two years. He got back to high-level racing at the Independent Man 100-mile/24-hour race in Rhode Island in 1982. He won the 100-mile in 14:45 and then took a long break, before going on to complete 133 miles while pushing George Gardiner to a new U.S. record for a road 24-hour.

In his own Summary, Nick publicized the fact that a well-known runner had been cutting ultra courses regularly for better times. (Unfortunately other runners are still doing this 35+ years later with a total lack of conscience). When Nick ran the 1983 Metropolitan 50 in Central Park, this runner who was not in the race, came onto the course and physically assaulted Nick an hour into the race, infuriated that he had been been “outed” for cheating. Despite having a bruised shoulder from the attack, Nick went on to complete the 50 miles in 6:14:01.

Nick also was involved in a long controversy over another character who never ran an official ultramarathon but achieved some fame in the general press for claiming to have set various records in solo runs he organized himself. Nick wrote articles in multiple running publications denouncing the guy as a fraud, and eventually the man faded from the ultrarunning scene. (More than three decades later, this same individual was involved in a defamation case in Georgia in 2014, and Nick was called as a witness, giving four hours of legal testimony in which he reiterated his expert opinion that the guy had a long history of being a con man.)

In 1983 Nick again went to Queens to run the 100-mile National Championship at Shea Stadium. He had the fastest 100-mile time of his life, finishing in 14:11:10, finishing second behind Ray Scannell of Massachusetts. Unfortunately, that year the course was set up incorrectly and the length runners covered ended being 101.25 miles, so Nick likely reached the true 100-mile mark that day in under 14 hours.

Beginning at midnight on Thanksgiving Day in 1983, Nick ran a unique 166-mile “Mr. Rogers Fun Run.” This was held on a point-to-point course in West Virginia, going over hilly roads from Wheeling to Charleston. The race had only 7 starters but included several top competitors. Nick passed David Horton to take over the lead at 65 miles and pulled away to win in 35:52:41, while everyone else eventually dropped out. This race was the first ultra in the modern era to openly offer prize money (previously, the rules of amateur sports meant that anyone who accepted money could be banned from running for being a “professional”); and he took home a winner-take-all $1000 prize.

Nick again ran the race in 1984. This time there were 13 starters and four men finished. Ray Krolewicz went out fast as usual, building a big lead as he went through the marathon in 3:03. The race had been shifted to summertime, though, and conditions were scorching. As the temperature soared into the 90s, Ray’s pace dwindled to a shuffle, and Nick overtook him at 77 miles. He soon opened up a sizable lead of his own, but encountered his own problems under a brutal afternoon sun. When he got to the 88-mile point in Parkersburg, he “got sick as a dog,” becoming violently ill from heat prostration. He ended up lying flat on his back for two hours in the town square, and Krolewicz and two other guys passed him during this period of distress. After that, Nick got back on course, walking until nightfall brought cooler conditions. Eventually he was able to resume a slow jog, and took back the lead. Despite throwing up ten times in the last 60 miles, he kept plugging away to win again, in 38:39, two hours ahead of Ray.

The following year, Nick made it three-for-three in West Virginia. This time it was Jack Bristol from Connecticut who took off at a torrid clip. Jack kept a blazing pace for so long that when Nick went through the 100-mile point in a speedy 15:02:37 himself, he was more than 8 miles behind Bristol. Luckily, several hours later Jack crashed badly, and Nick was able to pass him at 135 miles, while Bristol was sitting beside the road. Once he heard that Jack had dropped out for good, Nick was almost 20 miles ahead of everyone else. So after taking a 45-minute nap at 24 hours, he just walked the rest of the way to the capitol steps in Charleston, and still set a new course record of 32:42:28. Twenty-two runners started the difficult route that year, and only one other man finished it.

After winning this 166-miler, he was chosen as the U.S. representative in the 156-mile Spartathlon from Athens to Sparta in Greece. However, an injury before the race caused him to give up this trip, with Bernd Heinrich going to Greece as his replacement. Unfortunately, that was later followed by a non-running injury which put him out of action for a long time and ended Nick’s elite running career. In 1987 he hurt his back while trying to quickly move tons of boxes of books out of his basement when a furnace cracked and began flooding the cellar. (For 16 years, Nick was co-owner of a small independent bookstore and newsstand in Mechanicsburg, Pa.)

Over the next 8 years he managed to do a few marathons at a modest jog, but didn’t even try an ultra. A bad flare-up of the back in 1991 finally caused him to have major surgery on his spine. It wasn’t until 1995 that he could resume serious running again, though at a much lower level. His PR for 50 miles after this was 7:11:25.

A week before Christmas, 1999, Nick won a race for the final time. In a field of 46 runners, he did 4:09:44 to come in first in a 50K at Binghamton, N.Y. Two years later, he suffered the second really long interruption in his running. A month after doing a 50K in Central Park, New York City, in 4:35:09, he came down with a case of Lyme disease which damaged both knees. It was one of those cases where a runner gets told by multiple doctors that his knees are in such bad shape that “you’ll never run again.” Nevertheless, as sometimes happens, the medical opinions were wrong. After being knocked out of running for an extended period, Nick was eventually able to get back to regular jogging again in 2005.

However, this second serious non-running-related ailment knocked his abilities down another notch. Nick observes that he’s had three distinct ultra careers: once as a top competitor who was always a contender to win a race; then as a mid-packer; and now as a back-of-the-packer. It’s not a trajectory he’s liked, but he takes the demotions philosophically, saying, “Oh, well, you just keep doing the best you can.”

The only marathon he still hopes to do is the local Harrisburg Marathon, which he’s run 25 times, interspersed between his various layoffs. In 2013 at the age of 65 Nick ran it in an impressive 4:05:43 and the following year did it in 4:18.51.

In 2014, Nick said, “While many runners cross a finish line and swear they are never doing it again, when I cross a finish line I wonder when he could do it again.” He added, “I still have a great drive to see how far I can go, so I’m competing against myself in a little personal battle against the years. I look down at my watch and am amazed at how slow I go these days, but that doesn’t stop me.”

At the 2016 Crooked Road 24-hour race in Virginia, I shared the course with two legends, Nick Marshall and Ray Krolewicz. Sadly at that time I didn’t realize just how legendary they both were and I had no idea who Nick was as I lapped him over and over again. I won’t make that mistake again.

He stopped that day at 53 miles, but more recently completed 100 miles in 29:41:02 at The Sole Challenge in Fayetteville, Pennsylvania in May, 2017. That was a personal worst time for the distance, being 15 and a half hours slower than his PR. But, “you just keep doing the best you can.”

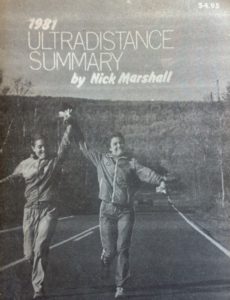

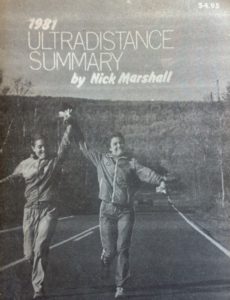

In 2017, Nick was inducted into the American Ultrarunning Hall of Fame. Included in the announcement was, “He is the first in the 14 year history of the Hall of Fame to be inducted not primarily based on pure athletic performance. . . . But Marshall’s unique, groundbreaking, Hall-of-Fame-ranking contribution to the sport of ultrarunning consists primarily in his role as organizer, correspondent, journalist, statistician, archivist. If Ted Corbitt was the father of American Ultrarunning, Nick Marshall was its caretaker, it’s nanny in its toddler years. And he remains its wise old man.”

International ultrarunning historian, Andy Milroy said of Nick, “One man did more than any other to establish American Ultrarunning as a cohesive community, linking it into its history. That man was Nick Marshall. In his Annual Summary he not only produced annual and all-time rankings for the different ultra disciplines, he researched and added marks by earlier runners, initially from the 1950s and 60s and then from the heydays of pedestrianism in the nineteenth century. Alongside this statistical wrap up was a commentary that brought the whole to life through its insights and humour. Over the following years ultra race directors and runners would send in reports that would add further to the summaries which were enlivened by Nick’s opinions on issues relating to the developing sport.”